Scientists CRISPR The First Human Embryos in the US (Maybe)

AS POWERFUL AS the gene-editing technique Crispr is turning out to be—researchers are using it to make malaria-proof mosquitoes, disease-resistant tomatoes, live bacteria thumb drives, and all kinds of other crazy stuff—so far US scientists have had one bright line: no heritable modifications of human beings.

On Wednesday, the bright line got dimmer. MIT Technology Review reported that, for the first time in the US, a scientist had used Crispr on human embryos.

Behind this milestone is reproductive biologist Shoukhrat Mitalipov, the same guy who first cloned embryonic stem cells in humans. And came up with three-parent in-vitro fertilization. And moved his research on replacing defective mitochondria in human eggs to China when the NIH declined to fund his work. Throughout his career, Mitalipov has gleefully played the role of mad scientist, courting controversy all along the way.

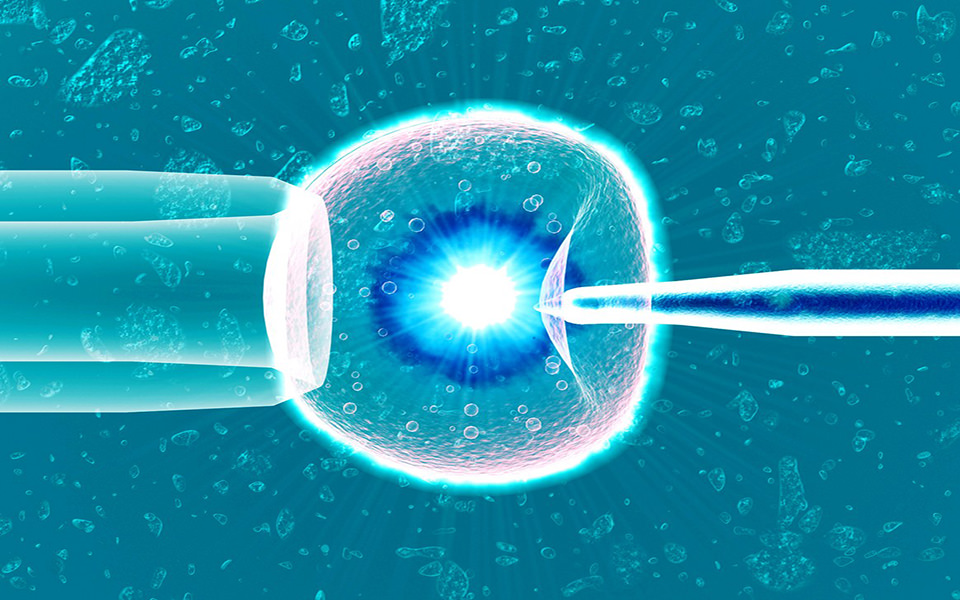

Yesterday’s news was no different. Editing viable human embryos is, if not exactly a no-no, at least controversial. Mitalipov and his colleagues at Oregon Health and Science University fertilized dozens of donated human eggs with sperm known to carry inherited disease-related mutations, according to the Tech Review report. At the same time, they used Crispr to correct those mutations. The team allowed the embryos to develop for a few days, and according to the original and subsequent reports a battery of tests revealed that the resulting embryos took up the desired genetic changes in the majority of their cells with few errors. Mitalipov declined to comment, saying the results were pending publication next month in a prominent scientific journal…

…Those obstacles aren’t insurmountable, and a particularly slippery slope winds between them. At the Aspen Ideas Festival last month, UC Berkeley biologist Jennifer Doudna, one of the people who discovered Crispr, stressed the need for a unified policy on germline editing before scientists really start doing it. “Once that begins, I think it will be very hard to stop,” she said. “It’ll be very hard to say, ‘I’ll do this thing but not that thing.’ And at that point, who decides?”