What Keeps a CRISPR Creator Up at Night

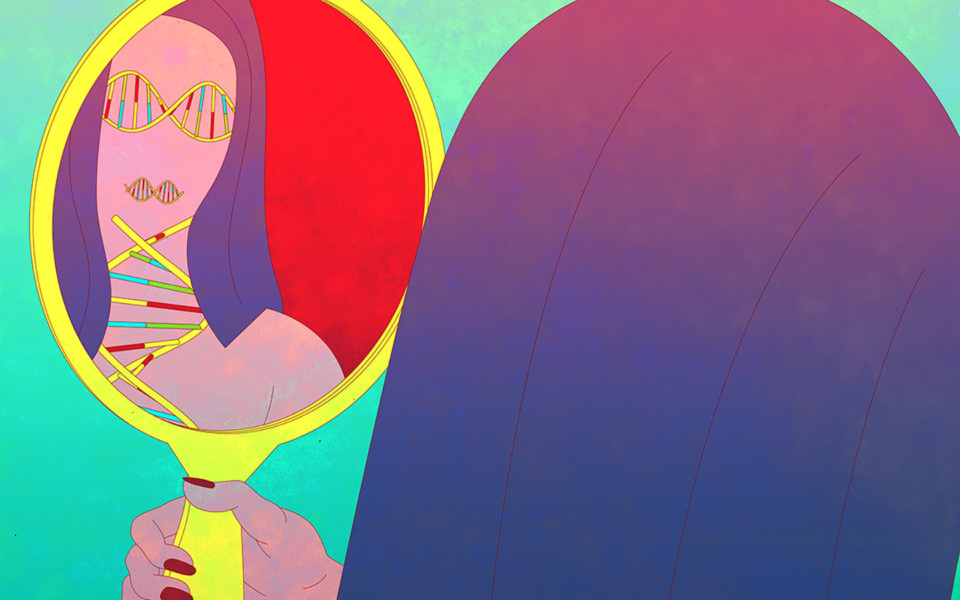

Gene-editing pioneer Jennifer Doudna’s new book reveals her dreams and nightmares about what she has unleashed.

Adolf Hitler came to her in a dream, wearing a pig’s face and asking excitedly about what she had just invented.

That nightmare — and her willingness to share the story — reveals a lot about Jennifer Doudna, a biochemist at the University of California, Berkeley, and her new book, A Crack in Creation. It’s the story of how she co-developed CRISPR-Cas9, a method for editing DNA that is almost as cheap and easy for biologists as cutting and pasting letters on a word processor.

Doudna and French microbiologist Emmanuelle Charpentier startled the bio-world in 2012 when they published their first CRISPR paper in Science. Almost overnight they had ushered in a long-anticipated moment when humans could more easily bioengineer themselves.

In the five years since, Doudna’s quiet life as a researcher has been upended by magazine cover stories and marquee appearances at TED and the World Economic Forum in Davos, plus talk of her and Charpentier as shoo-ins for a Nobel Prize. Investors and entrepreneurs have raced to start companies based on the technology, raising hundreds of millions of dollars, even while legal battles rage over the patents for technologies that others have refined after Doudna and Charpentier’s initial paper.

The CRISPR technique hijacks a mechanism used by bacteria to remember the identity of invading viruses: they cut and paste sequences of the interloper’s DNA. Doudna and Charpentier’s insight was that this process could be made to happen with DNA in any organism, including humans.